The

foreign farmer came back from his root-seeking

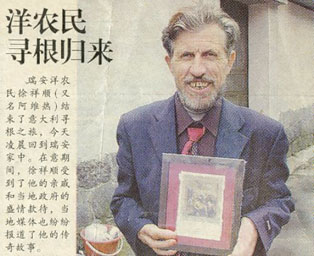

Early this morning, the foreign farmer Xu Xiangshun (Alvaro)

came back to his home in RUIAN city after ending his root-seeking

journey in Italy. During his stay in Italy, he had been warmly

entertained by his relatives and the local government and the local

medium had also extensively reported his legend.

taken from

Wenzhou Evening News 1.11.2001

A Chinese

Peasant's Italian Roots

By Ching-Ching Ni, Los Angeles Times

Culture: Xu

Xiangshun, taken to Asia at age 3, reconnects with his European

relatives but feels more at home in his stepfather's native land.

December 23,

2001 - - SHENAO, China -- He answers to the name Xu Xiangshun.

He speaks only the local Wenzhou dialect. Like many in this coastal

village of shoe assemblers, he chain-smokes, hacking and spitting on

the concrete floor.

But the thick

bronze curls on his head, the aquamarine eyes and prominent European

nose make it clear that Xu's parentage is anything but Chinese. In

fact, Xu is a full-blooded Italian who, through the vagaries of war

and helplessness, was raised and completely absorbed into the

Chinese peasant culture.

Chinese immigrants

have long assimilated into Western culture. Recently, as the country

becomes more internationalized, especially after its recent

acceptance into the World Trade Organization, more foreigners in

search of better business prospects are calling China home. But most

of these people enjoy comfortable expatriate lives unlike the total

immersion the 58-year-old Italian has gone through. He remembers

none of his native tongue--not even his Italian birth name. Three

times, the Chinese government rejected his request to return to

Italy to discover his roots.

Despite the

hardship and prejudice, he eventually settled in to his adopted

heritage. His knack for saving lives and his seeming ability to defy

death made him something of a mythical character in the village.

Then this year he

became a local cause celebre when a newspaper told his story, which

inspired a Chinese businessman in Italy to help him cut through the

red tape and return to his birth land.

There, he met his

five surviving aunts; a few were well into their 80s.

"Some of these

aunts had held me when I was a baby," Xu said, noting that although

an interpreter had to help them communicate, they wept together as

one family.

The reunion helped

Xu realize who he really is.

"I was Italian as

a child and Chinese as an adult," Xu said. "After I saw Italy again,

I still feel more Chinese."

The Boy From

Milan

Xu's Chinese life began more than half a century ago. His biological

parents were Italians from Milan. While his mother was pregnant with

him, his father, a soldier, was killed in World War II.

The young Italian

widow married the owner of the leather factory where she was

working--a Chinese man surnamed Xu from the village of Shenao near

the coastal city of Wenzhou. He had moved to Italy--a popular

destination for ambitious businessmen from his village--to start a

new life after the death of his first wife.

In his adopted

country, the Chinese man became a stepfather to the Italian boy.

When the child was 3, the Chinese father was beckoned home by his

family.

So in 1946, they

docked in this Chinese island village and began the painful struggle

to blend in and survive.

Their first son,

born in Italy, had died on the arduous journey. A second son, born

in China, died shortly after birth. A third child, a girl, lived.

But within two

years, Xu's mother died. The 32-year-old Italian woman never

adjusted to the harsh Chinese peasant life and the havoc of civil

war that ravaged the country. She left behind the 8-year-old Italian

boy and his half-Italian sister.

Xu's father had

lost three infant sons, including one from his previous marriage, so

he raised the Italian boy as the firstborn of the Xu clan. He

entered the child's Chinese name into the family genealogy records.

He concealed documents that connected the family to Europe. His son

did not know the papers existed until his stepfather passed away a

few years ago.

They had been

stashed away in a secret compartment inside the wall next to his

bed.

"We discovered

them by accident," Xu said. "Baby pictures and passports from

Italy."

The Italian boy

who grew up a Chinese peasant does not remember a word of his native

language. He thinks that the Italian name his mother called him was

"A-wu-re," though he only knows this vague Chinese pronunciation and

not the spelling.

It was tough

growing up so different in a world of similar faces. The other

children teased him often, so he quit school early to toil in the

family fields and tend to livestock.

"School was like

prison," Xu said. "I went from first grade to second grade and then

back to first grade again. It was hopeless."

He never learned

to read or write Chinese. He doesn't know how to express himself or

defend himself with words. He had to become his own best friend.

"I always knew I

was a foreigner," Xu said. "But when people called me that I would

hit them."

Now, he has a

sense of humor about his differences. "They say I look like Stalin,"

he said in his thick local dialect, flashing yellowed gapped teeth

and a bushy beard. His face is so deeply wrinkled and tanned that he

actually resembles a traditional Chinese farmer.

Knack for

Defying Death

Over the years the locals began to warm to him.

Although most

fellow villagers, including his relatives, make a living in shoe

factories converted from farmhouses, Xu insisted on the dangerous

job of drilling holes in the mountains to set up dynamite for road

construction.

Eight years ago, a

bundle of explosives detonated early and blew up in his face.

"If it had

happened to anyone else it would have been sure death," said Zhu

Zhonglong, a neighbor who has known Xu since they were teenagers.

Xu was knocked

out. When he woke up his hands were gone.

"I had only one

pinky left," Xu said. "Blood was everywhere. Everybody else was

freaked out. But I knew I had to find my fingers."

So he scavenged

through the ruble and collected four of his fingers.

The doctors

attached them, three on one severed hand and one on the other.

Though badly deformed, they can still grip a spoon and cigarette.

Throughout the

ordeal, folklore has it that the wai guoren, or foreigner, did not

scream for pain or shed a single tear.

No one seems

surprised. A traffic accident once left him underneath a truck. He

got up with only a mild concussion. Another time, a giant snake

coiled around his body like a rope. Xu hit the ground and rolled

down the rocky mountain slope, whiplashing the serpent and then

smashing it with a rock.

As a loner who

loves the river, Xu has practically become the village lifesaver. At

least three potential drowning victims owe their lives to him

because he dived into the rapids and scooped them out.

After he lost his

fingers, he found a job patrolling the village at night. For less

than $3 a day he stays up all night chasing burglars, an assignment

that leaves him poor but proud.

"My wife is scared

to death," Xu said. "Some of the bad guys carry big knives. I'm not

afraid. I'm a good fighter. Most of them just panic and run as soon

as they see my face."

Travel Permits

Rejected

In the 1970s he married a local woman, and they had three children.

His eldest daughter tumbled down a ladder and died. She was pregnant

at the time.

Three times in the

1970s he asked the government for permission to visit Italy. Three

times he was rejected.

"I was born in

Italy, I have the right to go back," Xu said. "How can they stop

me?"

According to his

friend and neighbor, Zhu, Xu ruined his chances because he was too

honest.

"They asked him,

'Why do you want to go to Italy? Don't you like China?' " Zhu said.

"He is a simple peasant. He does not know how to lie. So he told

them life in China is very bitter. That was it. One sentence, and it

was over."

Then this year a

local newspaper told his story, which touched the heart of a Chinese

businessman. Zheng Yaoting, who heads a Chinese Italian business

association in Milan, spent eight months making nearly 3,000 phone

calls to track down Xu's Italian relatives.

In October, with

the help of donations and a hefty security deposit to guarantee his

return, Xu journeyed to Europe for a brief reunion.

"My aunts and I

just cried and cried," Xu said after he returned from Italy. "We

have the same face and hair. But I can't understand anything they

are saying. I can't get used to their food. I don't even know how to

use a fork."

His wish now is to

send his children to Italy for a better life.

"That's just dream

talk," said his daughter, Xu Xianping, 24, rocking her infant in

their threadbare kitchen without even a refrigerator.

As for Xu, he says

he now realizes that China is his home. "I'm used to it."

|